Facial feature frustration: Learning with masks

Overcoming the obstacle

December 14, 2020

The introduction of face masks to the classroom, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic guidelines, has created unique challenges that both students and teachers must navigate through.

Face masks have covered the most vital facial feature used for communication: one’s mouth. Many find speaking and understanding others through a mask more difficult than expected.

“I remember that on the first day of school all my teacher’s voices seemed muffled. I was not used to hearing someone talk through a mask to an entire class. Now, some of my teachers tend to talk louder than normal so that the class can hear them. Others just speak to us behind face shields so they can take their masks off and have a clearer voice,” said junior Cody M.

As class periods have extended to 54 minutes, teachers must instruct with masks for a longer time frame. This can be distracting and tiring.

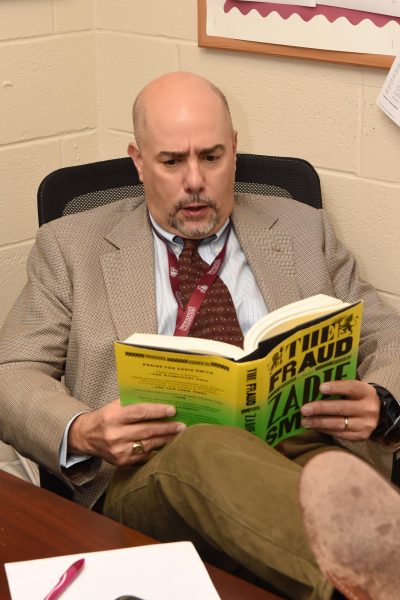

“[When] I try to project my voice, I find I [inhale] bigger breaths with the mask on. I also find, as I keep talking, my mask shifts around my face. If I adjust it, I can lose train of thought from time-to-time,” said history teacher Joseph Zaidinski.

Masks have also caused a lack of verbal participation in some classrooms, as students who dread public speaking are now forced to repeat themselves more frequently and speak louder.

“Students may feel more anonymous in a mask and they may want to be more of a spectator than a participant in class. Some […] may find comfort with wearing a mask to provide them with this anonymity,” said school psychologist Matthew Cardinale.

While masks have provided a level of anonymity, they also take away from any facial expressions many people use to convey their emotions.

“Facial expressions told me a lot. I could tell when students understood or when they were confused. As someone talked to me, I used their facial expressions to let me know when their point was made or when they were done speaking,” said Zaidinski.

Our minds are used to filling in context clues during conversations by interpreting the expressions and gestures of others. In terms of learning class material, many students find it especially difficult to understand their world language teachers without these cues.

“Spanish has been slightly more difficult this year. I hear less pronunciation of certain words. Before, I could just figure it out by looking at my teacher’s mouth moving or the emotions on her face. I can’t do that this year,” said Cody M.

Cardinale suggests that students and teachers should pay attention to body language to understand the context of words. He mentioned that noticing other facial features may help, too.

“We can rely on eyebrow and eye movements, but those too can send mixed messages. Eyes can certainly tell someone how another individual is feeling. However, they are a much less precise measure of someone’s emotions than a mouth or the lower portion of the face,” said Cardinale.

Another aspect of this year’s learning process is having less people in the classroom. The majority of classes this year have 13 or less students. This, along with social distancing guidelines, has affected in-class interactions between students and teachers.

“Class can definitely be awkward at times. With no one talking, I sometimes feel pressured to make conversation or raise my hand. Sometimes, kids won’t even reply to a teacher’s question. It feels like we’re not obligated to speak anymore,” said Mattera.

However, there are also benefits to smaller class sizes.

“ [Before], with 26 students, more opinions and point of views made for some great class chemistry. Now, having 13 students allows a teacher to focus on more students individually during a period,” said Zaidinski.

While students receive more attention from teachers on an individual basis, this new status quo may hinder students’ abilities to form connections with their peers.

“I think a reason [for a lack of connection] might be that activities normally discussed are now put-on pause. For example, I coach in another district and sports was always a great bridge of communication with student-athletes. Other activities students were involved with helped spark conversation, too. Now, we don’t have that happening anymore,” said Zaidinski.

Cardinale considers that improved grades, improved understanding of the material, and increased motivation, are results of connections between students and teachers.

Mask wearing has affected these interactions that are vital to the learning process.

“I’m not as close with my teachers this year as I was with them last year. Maybe it’s because they can’t see me smiling at their jokes under my mask,” said Cody M.🔳